Going After Cacciato (winner of the National Book Award in 1979) was widely acclaimed as one of the most powerful and emotionally vivid novels about Vietnam. Now, writing with the same sharp, richly expressive language, the same edgy dark humor and complete honesty, and the same rawness of nerve and energy, Tim O’Brien gives us an equally powerful novel about growing up as a child of anxiety—thebig anxiety, the one that’s been with us since the fifties, when we finally realized that Einstein’s theories translated into Russian.

It’s 1995 and William Cowling is digging a hole in his backyard. He is forty-nine, and after years and years of pent-up terror he has finally found the courage of a fighting man. And so a hole. A hold that he hopes will one day be large enough to swallow up his almost fifty years’ worth of fear. A hole that causes his twelve-year-old daughter to call him a “nutto,” and his wife to stop speaking to him. A hole that William will not stop digging and out of which rise scenes of his past to play themselves out in his memory.

The scenes take him back to his quietly peculiar adolescence (No. 2 pencils had a surprising significance), to his college days, down into the underground, and up through several stabs at “normal” adulthood . . . they take him from Montana to Florida, from Cuba to California, from Kansas to New York to Germany and back to Montana as he makes him way through an often mystifying—but just as often hilarious —labyrinth of fears and desires, obsessions and obligations, blessed madness and less-than-blessed sobriety . . . they take him into the lives of a shrink who’s a whiz a role reversal and of a dizzying eccentric cheerleader; of radical misfits and misfit radicals; of an ethereal stewardess (the traveling man’s dream); and two guerilla commandos who mix shtick and nightmare in their tactical brew. And each scene is a reminder of the unbargained-for-terror that has guided him to the bottom of his hole. For this digging is his final act of “prudence and sanity”—he’s taking control, getting there first, robbing his fears of their power to destroy . . . or so he believes. But is this act really sane? Is his daughter’s estimation of his emotional well-being (“pretty buggo, too”) the only truly sane statement being made? Is sanity even the issue? In the dazzling final scenes, William turns from the hole—from his past and from his future 0 to himself, digging deeper and deeper to find his answers.

The Nuclear Age is pyrotechnically funny and moving, courageous and irreverent. It takes on our supreme unacknowledged terror (whose reality we both refuse to accept and all too easily accommodate ourselves to), finds it lunatic core, and shapes it into a story that speaks of, and to, an entire age: our own, our nuclear age. It is an extraordinary novel.

**

It’s 1995 and William Cowling is digging a hole in his backyard. He is forty-nine, and after years and years of pent-up terror he has finally found the courage of a fighting man. And so a hole. A hold that he hopes will one day be large enough to swallow up his almost fifty years’ worth of fear. A hole that causes his twelve-year-old daughter to call him a “nutto,” and his wife to stop speaking to him. A hole that William will not stop digging and out of which rise scenes of his past to play themselves out in his memory.

The scenes take him back to his quietly peculiar adolescence (No. 2 pencils had a surprising significance), to his college days, down into the underground, and up through several stabs at “normal” adulthood . . . they take him from Montana to Florida, from Cuba to California, from Kansas to New York to Germany and back to Montana as he makes him way through an often mystifying—but just as often hilarious —labyrinth of fears and desires, obsessions and obligations, blessed madness and less-than-blessed sobriety . . . they take him into the lives of a shrink who’s a whiz a role reversal and of a dizzying eccentric cheerleader; of radical misfits and misfit radicals; of an ethereal stewardess (the traveling man’s dream); and two guerilla commandos who mix shtick and nightmare in their tactical brew. And each scene is a reminder of the unbargained-for-terror that has guided him to the bottom of his hole. For this digging is his final act of “prudence and sanity”—he’s taking control, getting there first, robbing his fears of their power to destroy . . . or so he believes. But is this act really sane? Is his daughter’s estimation of his emotional well-being (“pretty buggo, too”) the only truly sane statement being made? Is sanity even the issue? In the dazzling final scenes, William turns from the hole—from his past and from his future 0 to himself, digging deeper and deeper to find his answers.

The Nuclear Age is pyrotechnically funny and moving, courageous and irreverent. It takes on our supreme unacknowledged terror (whose reality we both refuse to accept and all too easily accommodate ourselves to), finds it lunatic core, and shapes it into a story that speaks of, and to, an entire age: our own, our nuclear age. It is an extraordinary novel.

**

Dirty Brothers: The Complete Series

Dirty Brothers: The Complete Series Chosen By The Berserker (Warlords 0f Farian Book 5)

Chosen By The Berserker (Warlords 0f Farian Book 5) Journee's Journey

Journee's Journey Vigorish

Vigorish Creative Matchmaker (The Inscrutable Paris Beaufont Book 6)

Creative Matchmaker (The Inscrutable Paris Beaufont Book 6) The Killing of Worlds (Succession #2)

The Killing of Worlds (Succession #2) Blackout: Book One (The Leather & Lace Duet 1)

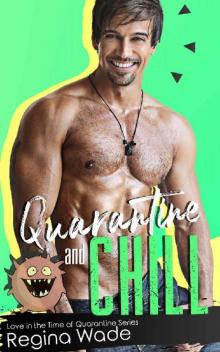

Blackout: Book One (The Leather & Lace Duet 1) Quarantine and Chill

Quarantine and Chill